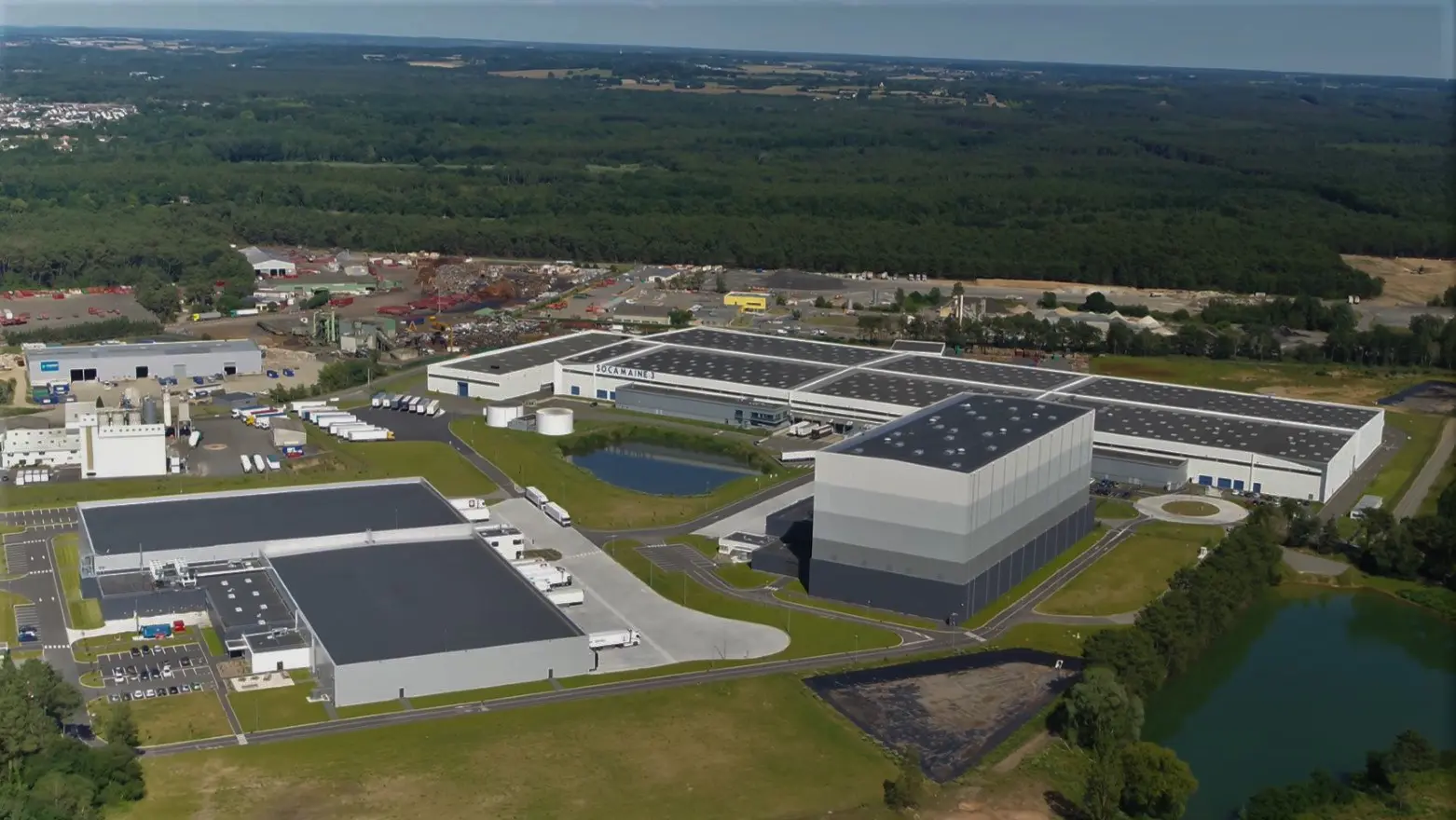

Since the municipal elections, the change of government and the closure of the Climate Convention, logistics has entered the political discourse (content in French). Embodied by Amazon’s giant distribution centres, e-commerce has been the subject of much criticism. In particular, it is criticised for its environmental and social impact. Even if some concerns are legitimate, a virtuous warehouse is nevertheless possible, thanks to the so-called “intensive” logistics model.

Goals: save time and space

In logistics, there are only two sources of cost:

- Time, which is often a reflection of the distance to be covered;

- Space, because building space is scarce.

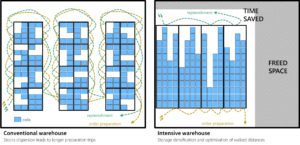

Every pallet or parcel consumes time and space for the logistician. It is in everyone’s interest to reduce this consumption. Every minute spent in a truck represents costs for the end customer and CO2 emissions for the planet. Each square metre occupied is responsible for a greater artificialisation of the land and entails a land and tax cost for the distributor.

At a time when awareness of environmental issues is at its peak (content in French), guaranteeing the level of service expected by consumers (24-hour delivery, reverse logistics, etc.) seems paradoxical. However, it is possible to reconcile these apparently contradictory objectives by optimising the consumption of time and space within distribution centres. How can this be done? By increasing the density of stocks: this is the philosophy of the “intensive” logistics model.

The philosophy of the “intensive” logistics model: densify storage to save time and space.

The Automated High Bay Warehouse

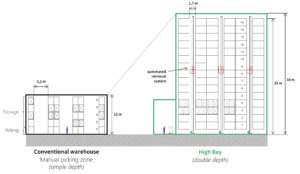

For years, “conventional” pallet warehouses have been built to a ceiling height of around 12 metres, which is the maximum height reached by forklifts. However, this ballet of forklifts is time and energy consuming. Worse still, it is not uncommon for the forklifts to hit the shelves and cause dramatic collapses for the forklift drivers.

To increase the density of storage, one solution is needed: building high up. The “Automated High Bay Warehouses” are buildings that rise up to 45 metres high, with 20 levels of pallets on top of each other (compared to 5 in the conventional case). Obviously, the handling of the loads can no longer be done manually. Therefore, several machines are used, the so-called “stacker cranes”, which can each place and remove up to 50 pallets per hour by means of translational movements in the storage aisles.

A high-rise warehouse under construction, a steel cathedral.

The space saving is obvious: four times less floor space is used and half the volume, with aisles and empty spaces restricted to the strict minimum. Moreover, thanks to fully computerised management, operations become more reliable, more precise and faster. Inventories are no longer necessary, and the risk for operators is reduced to zero. Finally, energy consumption is greatly reduced (no lighting required, minimum volume to be maintained at controlled temperature, etc.).

The Automated High Bay Warehouse.

This type of infrastructure has been very common in Germany for

several decades, but is still rare in France. However, if it is well designed, a return on investment can be achieved after about five years. Moreover, contrary to a well established idea, these investments are not made at the expense of flexibility. The shelving is fungible, i.e. it can be transformed if the logistics flow changes.

The challenges raised by the ‘intensive’ logistics model

Even if it provides a way out of the sterile opposition between logistics and ecology, the intensive warehouse cannot succeed without a global political approach.

Relocating the industrial tool

First of all, the ecological footprint of logistics remains very large. Some players, too few in number, are acting locally to equip their warehouses with solar panels and minimise the impact on biodiversity. But this is not the main issue. On the whole, the carbon footprint of logistics stems mainly from an industrial model that is reaching its limits: international just-in-time.

Promoting European competitiveness encourages the regionalisation of supply chains, which has a much greater environmental and social impact. Producing locally means creating jobs and reducing the nuisance associated with the transport of goods. The development of rail and waterway freight, which the government wants, is also a step in the right direction.

Supporting retailers in the digital transition

Moreover, e-commerce, like any major economic development, represents both a threat and an opportunity for traditional retailers. In the same way that the CD was not saved by the Hadopi laws, it is not by banning warehouses that we will convince the French to buy in town centres. This is all the more true in this period of health uncertainty that weighs heavily on the consumer shopping experience.

But all is not lost for physical shops, on the contrary: with an effective city policy, many cities, such as Annecy or Amiens (content in French), have strongly revitalised their shopping streets. Thanks to the innovative ecosystem of logistics start-ups, shops can now offer omnichannel experiences (content in French) on a par with the biggest players. Banning the warehouse itself would only lead to it being moved to the borders of France, at the cost of increased pollution on the way.

Improving the attractiveness of the logistics sector

Finally, the impact of automation on employment is probably the main subject of opposition. This is a recurring debate on the notion of “progress”. However, elected representatives are little aware of the difficulty of recruiting for this type of function. When a traditional platform opens its doors, hundreds of handlers have to be found, jobs that are hard and poorly paid. 62% of recruitment projects are considered “difficult” (content in French) in this sector, which is not very attractive.

The automated warehouse does not make operators disappear. On the contrary, it is making their jobs evolve in the right direction, by offering employees ergonomic workstations and more rewarding career options, particularly in order preparation or maintenance. A fact rare enough to be highlighted: the automation projects carried out by SDZ ProcessRéa are the result of a consensus with the employees concerned.

Far from simplifying speeches, logistics therefore needs political courage to promote virtuous economic development, both for people and for the environment.

To go further: see the interview with Etienne Page (content in French), Director of Development of SDZ ProcessRéa, on Stéphane Soumier’s show.